FASB to the Rescue? Yes, FASB to the Rescue

In the world of tax equity investing, corporations need to consider how to account for the investments and report them to their stakeholders. Federal tax credit programs encourage private sector investment in a wide variety of projects that the government deems important, including renewable energy, low-income housing, and the preservation of historic buildings. But a labyrinth of accounting complexity often stands in the way of this critical private sector investment even as the federal government seeks to encourage it. There is one institution that has the capability to dramatically mitigate this quagmire – the Financial Accounting Standards Board (“FASB”). FASB can come to the rescue and unlock a wave of private sector investment by simplifying and clarifying the accounting treatment of these investments.

Most companies will report and issue financial statements using Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (“GAAP”). Though tax equity investing has been around longer than many people realize, there has historically been little guidance or accounting pronouncements related to these investments. This creates a void whereby certain GAAP principles are then, by default, applied to tax equity investments. While all tax equity investments are economically net positive to the investing community, these default GAAP rules often create bizarre financial reporting results. This lack of accounting guidance and clarity often proves prohibitively difficult to sort out by overworked accountants and is standing in the way of broader corporate adoption of tax credit programs, such as the solar Investment Tax Credit (“ITC”). The solar ITC seeks to add significant amounts of renewable energy to our power grid. Moreover, the application of some of these default rules distorts the true economics of the investment and artificially impacts the operating earnings of the investors.

FASB guides companies as they implement GAAP. The equity method of accounting is correctly applied to all tax equity investments. From there, the complexity often begins.

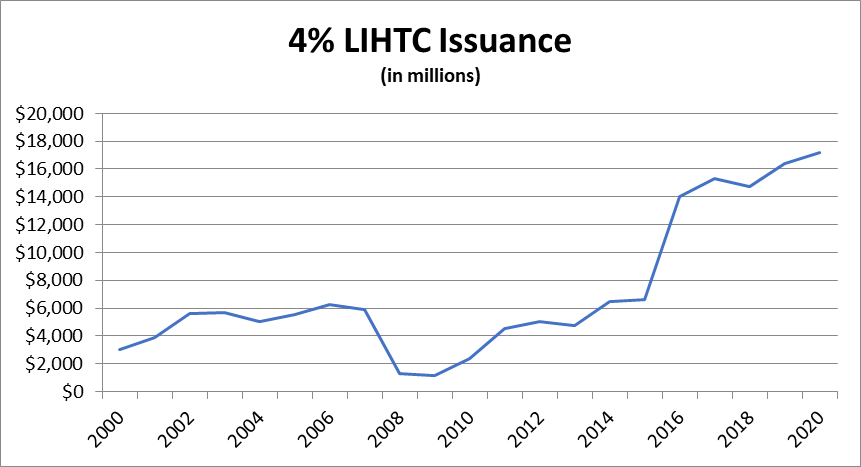

FASB is responsible for establishing and improving these GAAP methodologies. FASB is already aware of the accounting complexity associated with tax equity investments, and there has been some recent improvement and clarity for certain types of tax equity investment. One example that FASB has addressed is tax equity investments in the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (“LIHTC”) program. In 2014, FASB announced Rule Update No. 2014-01, which allows LIHTC tax equity investors to use a GAAP method called proportional amortization. As the chart below illustrates, the adoption of proportional amortization accounting treatment for LIHTC investments has unlocked material investment in this critical market. FASB should expand this treatment to the broader tax credit market.

In General, GAAP accounting for investments falls under one of three main categories: the cost method, the equity method, and the consolidation method. When it comes to tax equity investments, GAAP rules demand that we utilize the equity method of accounting.

All tax equity investments are driven by two goals: first, to enhance corporate earnings and cash flow by taking advantage of tax credits and other benefits proffered by Congress; and second, to invest in projects that fulfill the ESG aspirations of a company. The structure of tax equity investments is typically driven by the tax rules that govern a particular incentive. In all instances, the tax equity investment is made through an entity taxable as a partnership. Even though the tax equity investor will usually have a 99% interest in the tax equity fund, the equity method is followed in most instances because the investor interest in the tax equity fund possesses minimal management or decision-making rights. This allows the tax equity investor to receive 99% of the tax credits and other tax benefits (such as accelerated depreciation in the case of solar ITC). Even though the tax equity investor has a 99% ownership interest, they typically don’t have management responsibilities or significant control over the day-to-day operations of the project. That role is taken on by the sponsor of the project. Because of this, the equity method of accounting will be the default GAAP method most companies utilize to account for federal tax equity investments.

Within this regime of treating the investment under the equity method, there are two choices a corporation can make: the flow-through method or the deferral method. Both methodologies come with inadvertent complexities that often kill potential transactions. Under both options, the initial investment is recorded as an investment in a partnership on the books of the company.

The flow-through method of accounting has served as the default to account for tax equity investments. Under this approach, the receipt of the tax credits by the investor simply flows through to the company’s tax provision and has no impact on the book value of the investment. Unfortunately, impairment issues often arise and can prove insurmountable.

While the flow-through method of equity accounting is relatively straightforward, there is no mechanism to account for an investment where most of the financial returns are tax credits and other tax benefits. Under the equity method of accounting, the investor records their investment at cost as an asset. Any cash distributions or financial returns are first applied against the investment cost, reducing the investment’s book value. Then, any income or loss is recognized on the company’s income statement. Once the investment’s book value is reduced to zero, any further distributions or financial returns are recognized as a component of net income before taxes. While this sounds straightforward, it can get complicated when tax credits and tax benefits (not cash) are the primary return metric. Tax credits and tax losses (not book losses) under the equity method don’t reduce your book investment. Instead, these tax benefits flow through to the investors and are typically reported “below the line” as part of net income after taxes. As a result, the company reports a reduction to income tax expense and a reduction to their income taxes payable since the federal tax credit reduces how much they owe to the federal government and is effectively a cash equivalent of paying your taxes. On the surface, this is a great answer as a direct reduction to income tax expense would positively impact the company’s Effective Tax Rate (“ETR”). However, the major issue is the initial investment sitting on the company’s books. As mentioned, the primary benefits to tax equity investors are the tax credit and tax losses. While there was some residual cash flow paid to the tax equity investor in the form of preferred returns and call/put options upon investment exit, the investor still ends up having a majority of the initial investment on their books. It’s at this point that the dreaded “I” word comes up, and which no CFO wants to hear: impairment.

Because of the high book value of the investment sitting on the company’s financials, the most common way to remove the investment is to write it down through an impairment charge. The impairment expense is reported above the line and can often be reported as part of Net Operating Income, an important performance metric for many corporations. We now have a positive impact “below the line” from the tax credits and tax losses but a negative impact “above the line” from the impairment. In total, the overall impact is net positive, and there is a net positive impact to earnings per share (“EPS”) as the investments are economically accretive. However, this financial statement geography issue has given some corporate investors pause. Questions such as materiality and other factors play into a corporation’s tolerance to impairment, but in general, executives and corporate directors have found this to be a major issue.

The deferral method is an attempt to reduce the impairment consequences of the flow-through method. Unfortunately, this does not completely mitigate the impairment issue, particularly if the price of a tax credit is more than one dollar per credit (as is the case with most solar ITC funds).

Under the deferral method of equity accounting, the flow-through of the ITC is a direct reduction to the tax equity investment’s book value with a corresponding reduction to income taxes payable (i.e., there is no income tax expense reduction). This is somewhat of a tradeoff because there won’t be a reduction to the ETR, but most, if not all, of the investment can be written down, often avoiding any impairment charge. This does not necessarily do away with the impairment issue because certain federal tax equity investments, like solar ITC, are invested at a premium to the credit (for example, 1.20 per dollar of ITC), so there would still be 20 cents of book investment that could be impaired, to the extent future expected cash flows from the investment would not exceed the 20 cents. While the deferral method may be a better answer than the flow-through method, it does not completely mitigate the impairment issue.

In a typical ownership structure, after a certain period, the tax equity investor’s 99% ownership interest will “flip” down to a significantly lower percentage (usually 5%). When the investor hits their targeted return yield or reaches a specific calendar date, the flip occurs, and the tax equity investor ownership interest is purchased by the sponsor. After this flip, the tax equity investor exits the deal. This makes tax equity investments, in the eyes of GAAP accounting, what is known as a Variable Interest Entity (“VIE”) because of the ownership interest “flip.”

The application of VIE accounting rules proves to be the final straw for many prospective investors. This is because VIEs are subject to Hypothetical Liquidation at Book Value (“HLBV”) accounting, which only compounds the risk of impairment charges and complexity under both the flow-through and deferral methods. The complicated methodology is often the final, insurmountable hurdle and is proving to be a meaningful headwind for these government encouraged investments.

Since the investments are considered a VIE, they are subject to another GAAP rule known as HLBV accounting. In short, HLBV says that as of balance sheet measurement periods (quarterly and annual), you must determine what your VIE investment value would be at that time if it were to liquidate all its assets (assuming they’re worth their book values) and pay off all its debts. As discussed in a previous article, HLBV applied to tax equity is a solution seeking a problem that does not exist.

The main takeaway on HLBV is that it can cause book values to be written back up based on their project-level book values under the terms of the project partnership agreement assuming the project is liquidated at the point in time being measured. Initially, this inevitably results in an artificial write-up and overstates operating income. Ultimately, the investment must be written back down over the life of the investment through impairment charges, which is confusing, costly, and unnecessary.

These accounting complexities can create the illusion of a bad investment and understates a company’s true operating earnings. Furthermore, it does not reflect the economic reality of what tax equity investors are seeking to do, which is to lower their federal tax liability and contribute to funding investments that the federal government seeks to promote.

Proportional amortization, which was adopted by FASB for treatment of low-income housing tax credit investments, offers investors relief from these accounting nightmares. It does away with the impairment issues and the need to apply HLBV to the investment.

Proportional amortization alleviates this income statement geography issue. The proportional amortization method allows the LIHTC tax equity investor to recognize the tax benefits (credits + losses) and any corresponding investment amortization “below the line.” The investment is realized in proportion to the amount of tax benefits received each year over the total expected tax benefits of the tax equity investment. Essentially, the net benefits each year from the investment will be recognized as a component of income tax expense. This reflects the economic reality and accurately shows the effects to the ETR. It makes sense FASB adopted this method for low-income housing tax credit investments. There is no reason a tax-motivated investment should impact anything other than the investing company’s tax provision.

If FASB were to expand the proportional amortization treatment across the spectrum of tax credits, it would unlock a wave of pent-up demand. Last September, FASB met to discuss the broader adoption of the proportional amortization method to other types of tax credit investments, and in a positive step forward, they added this to their Emerging Issues Task Force Agenda. FASB really can come to the rescue of the tax equity market. We sincerely hope they seize the initiative and follow through.

Related Posts

Forbes Article – How Corporate Boards Can Avoid ESG Investing Pitfalls

Aug 4, 2022

By George Strobel, Forbes Financial Council Member Corporate boards are under intense pressure from shareholders and other constituents to invest in ways they can tout their environmental, social and governance (ESG) […]

Fast Company: Trump is coming for renewable energy—but the solar industry isn’t worried

Mar 24, 2025

By Kristin Toussaint Solar industry experts say it has too much Republican support, and makes so much sense economically, that the solar industry will keep growing. President Donald Trump has been […]

Monarch Private Capital Launches Its Own Podcast, Monarch Perspectives

Nov 30, 2023

New podcast series offers insight for investors and developers interested in tax credits and tax equity investing Monarch Private Capital, a nationally recognized impact investment firm that develops, finances, and […]